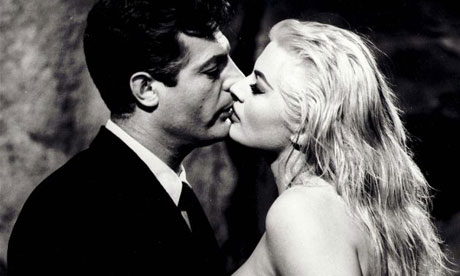

From its opening scene, in which a helicopter lifts an outstretched statue of Jesus across the roofs of Rome, to its final one, in which partygoers find a monstrous fish on a beach, Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita is full of memorable images. Even those who have never seen it know the scene where Anita Ekberg wallows at night in the Trevi fountain. These ever fresh iconic cinema moments are 50 years old now, and both Rome and Rimini (the film director's birthplace) have been marking the anniversary in style. All this is a world away from the furore when the film was finally released in 1960 - when Fellini was spat on "in the name of the fatherland" at the Milan premiere, challenged to a duel by an outraged Roman, accused of inciting vice and immorality by the Vatican newspaper and saw fights break out in the audience after showings. The film was not even universally admired by liberal critics. An early Guardian review observed that the film lasts three hours, "of which two are superfluous", before offering the withering judgment that "even the best sequences rise no higher than the level of good journalism". Today the verdict is different. Fellini's film about Rome's shallow materialism is widely adjudged a masterpiece and routinely numbered in moviedom's all-time hit parade. Fifty years on, La Dolce Vita's preoccupation with celebrity, sex and hedonism seems a presciently modern cultural turning point. But its moral artistic core seems old-fashioned now - to our loss.