One of the daffiest aspects of W.E., Madonna's deeply daffy film about Wallis Simpson, is the way our heroine keeps popping up as a peculiarly soignée ghost. Clad in a little black dress and pearls, she dispenses fashion tips and lifestyle aperçus to her younger namesake, who's having a bit of a breakdown that coincides with her Simpson-fixation, in 1990s Manhattan. Murmured words of spectral wisdom include: "Attractive, my dear, is a polite way of saying a woman's made the most of what she's got," and, "The most important thing is your face. The other end you just sit on."

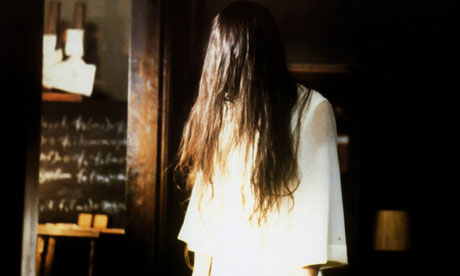

This is perhaps the battiest but also the most diverting element in the film, and one I wish Madonna had explored at more length, if only because the Wallis bespoke-ghost is the best dressed phantom since Constance Bennett modelled an entire afterlife's worth of 1930s wardobe in Topper. It makes a refreshing change from Sadako in Ringu, and all those other creepy Japanese spectres who have been dictating the posthumous fashion look of late with their lank, unconditioned hair, bottom-of-a-well complexions and tragic manicures. And it does make you wonder – if only Sadako and her sisters had been taught to make the best of what they'd got, perhaps they wouldn't have been so hellbent on wreaking horrible revenge on the living.

Sadly, any hopes that the Madonna-style ghost will trigger a revolution in comeback couture will be knocked on the head next month, when it's back to business as usual with an evil female from beyond the grave. The Woman in Black may dress in black, like Wallis, but her fashion sense can only be described as depressing. Susan Hill's novel has already inspired a long-running West End play, and was previously adapted for British TV by Nigel Kneale in 1989; a near-legendary production that still has veterans of the original TV screening exchanging nervous whispers about "that scene". The new version, directed by Eden Lake's James Watkins and adapted by Kick-Ass scribe Jane Goldman, stars Daniel Radcliffe as a young lawyer called Arthur Kipps (a name that makes you wonder if it might turn out to be a sort of supernatural sequel to Half a Sixpence) who has a close encounter with a female ghost with a horrible agenda, and an expression full of "the purest evil and hatred and loathing".

Indeed, you have only to cast a glance over the history of ghost movies to see the malevolence with which they're seething is more often female than male. Malign masculine presences such as Peter Quint in The Innocents, Emeric Belsaco in The Legend of Hell House, or franchise phantoms such as Freddy Krueger and Candyman are exceptions rather than the rule. Think of male ghosts in the movies, and you're more likely to summon up fond memories of rufty-tufty Rex Harrison as Captain Gregg in Joseph L Mankiewicz's sublime The Ghost and Mrs Muir, in which he is pipe-sucking protector and literary muse to widowed Gene Tierney. Or, in a more recent variation, Patrick Swayze as Sam Wheat in Ghost, who can't go into the light until he has made sure his live-and-kicking girlfriend (Demi Moore) is not just safe from harm, but 100% convinced of his love.

Even Britfilm has its benign male spectre – Alan Rickman in Truly, Madly, Deeply, whose modus operandi is, rather than terrorising his bereaved girlfriend, behaving like a regular partner by inviting his ghostly pals back to her place to watch videos, and generally behaving like a slob. Like latterday vampires of the bloodless Twilight persuasion, these are the sort of ghosts you could probably take home to meet mum without giving her conniptions.

The movie versions of wicked woman wraiths, on the other hand, follow in the spectral footfalls of the white ladies, bloody Marys and succubi of folklore and urban legend, all waiting to entrap unwary men, possess innocent young maidens, or slice up the teenagers who summon them. Female ghosts are often perverted mother figures who exhibit infanticidal tendencies or homicidal jealousy in place of the expected maternal nurturing qualities, such as the entity in Lewis Allen's delectably spooky The Uninvited (1944), in which Ray Milland and his sister buy a house on a Devon clifftop and find themselves caught up in a supernatural Rebecca-type scenario.

Or, like the shades in Stir of Echoes, The Sixth Sense, J-Hôra movies such as Ringu or Ju-On, or the Thai film Shutter, they seek vengeance on the people (usually, but not always, men) who wronged them, which may sometimes make them slightly more sympathetic as their story unfolds, but doesn't stop them from scaring innocent characters to death with their sickly pallor or their alarming habit of dragging themselves across a room on all-fours.

The ghosts of old women are viewed as particularly repulsive. In a scene that has long made me uncomfortable for all the wrong reasons, Jack Nicholson kisses a sexy nude woman in The Shining's room 237, only for her to be transformed by the hotel's malignant forces into – horror of horrors! – a mouldy old crone. What could be worse? Especially if, like me, you're fast approaching that age and starting to take it personally. The old ghost in Mario Bava's Black Sabbath is all the more terrifying for looking like a decrepit waxwork (and bears a faint resemblance to Meryl Streep in The Iron Lady), while the creepiest scene in Alejandro Amenábar's The Others is when Nicole Kidman sees her small daughter transformed into a knackered hag.

Old ladies represent all that's most frightening in a society where youth is viewed at something to be preserved at all costs, especially for women. It's assumed the elderly are vampirically envious of nubile flesh, so much so that in films such as Burnt Offerings, Skeleton Key and Hausu, ghostly crones actively seek to occupy or consume the bodies of youngsters in order to regenerate their own physical forms.

But a woman is evidently a terrifying thing no matter what her age, for at the other end of the spectral age spectrum is the little girl ghost, as seen in The Shining's twins, the creepy little fair-haired child in Bava's Operazione Paura or Mia Farrow's nemesis in Full Circle, which starts off with a botched tracheotomy and only gets worse. The idea that such an innocent butter-wouldn't-melt appearance may be a front for undead depravity is just as discomfiting as the scary old lady.

In any case, ghosts are unusual among movie monsters in that they're more often female than male, perhaps because their origins lie in the Gothic romantic tradition, which so often features haunted houses, madwomen in the attic and sinister nocturnal goings-on. It's a particularly female branch of the horror genre, but appeals to male viewers as much as to female ones since it subverts the conventional view of woman as a passive, obedient creature and supposes that the angry, violent, retributive urges suppressed in life may emerge after death in twisted malevolent form. As Colette Balmain, author of Introduction to Japanese Horror Film, writes: "The reason for the success and ubiquity of such female ghosts is a mixture of female desire, and fear of such empowerment."

Unless, of course, she's the ghost of Wallis Simpson, a self-help big sister, telling us: "Darling, they can't hurt you. Unless you let them."

• The Woman in Black is released on 10 February. W.E. is released on 20 January