The horrors of tunnel warfare are key to Sebastian Faulks's first world war novel, Birdsong. Much of the action is set beneath no man's land in a terrifying world where soldiers dug, listened for the enemy and laid explosives in the hope of helping their compatriots above ground.

To create a realistic portrayal of this deadly underground battle for the book's television adaptation, the producers built an accurate replica of part of the vast network of tunnels. They believe this is the first time this has been attempted.

The detailed reconstruction was aided by Peter Barton, a first world war archaeologist and historical writer, who has made the subject his life's work. Barton, employed as a consultant on the drama – judged too difficult to film for years – supplied Birdsong's director, Philip Martin, with scale drawings and plans from his excavations. Only then could a set of tunnels be built in a Budapest studio.

Martin said: "The tunnelling was not something I'd seen on screen before. The dimensions in the drama are correct. We tried very hard to get the details right. You have to remember, this was a massive industrial process, they were sawing beams and planks to exact proportions above ground. It was the British empire at its peak.

"I really suffer badly from claustrophobia, I would rather walk than go on a tube. We were filming the tunnel scenes in a very small space, it was incredibly tricky."

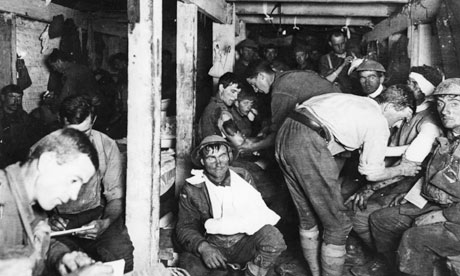

By 1916, the British had 25,000 tunnellers, mostly former coalminers, some from the dominions. The network they created stretched for 300 miles said Barton.

Just before filming started, Barton took the actors who play the book's protagonist Stephen Wraysford and his comrade Jack Firebrace – a miner, employed to listen for the enemy and plant mines under the German trenches – on a guided tour around a newly opened tunnel at La Boisselle on the Somme battlefield. This was three miles from the site of the fictional tunnel in which Wraysford worked.

"If they really wanted a taste and flavour of it, it's the only place in the world," Barton said. "They did cope. I went first, Joe [Joseph Mawle, who plays Firebrace] after me. As we slid into the tunnels he looked a bit pale and he said, give me a minute… we were down there about an hour, it was very constricted."

A poem is inscribed on one of the tunnel walls, the only one Barton has ever discovered. The author, whose signature is illegible, scratched: "If in this place you are detained, don't look around you all in vain, but cast your net and you shall find, that every cloud is silver lined… Still." Barton said: "They [the actors] were very visibly affected. They went very quiet indeed."

Bodies of many tunnellers remain entombed in the complex at La Boisselle, which was called the Glory Hole by British troops. It is in an untouched state, with pick marks still visible on the walls. Local landowners agreed last year to let the La Boisselle study group open it.

La Boisselle is the village where the German advance that opened the war was stopped by French troops on 28 September 1914. This led to the use of tunnelling in an attempt to undermine the positions of the enemy, a military art used for thousands of years. Both sides combined tunnelling with explosives, building chambers under key defensive positions to blow breaches in the line.

Working in silence, the British also used explosives to trap enemy tunnellers, often just feet away. Barton calls it "a deadly blind cat-and-mouse game".

Barton, whose book credits include Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers' War 1914-18, said his approach was to focus on individuals and their families – not unlike Faulks's novel. He said the conditions the men involved faced and their bravery were "humbling".

In his introduction to Birdsong, Faulks wrote that he only learned about tunnel warfare in 1988 when books about the armistice 70 years earlier were published. "I had previously no idea that beneath no man's land, in tunnels so low you could not stand up, another war had been fought: a hell within hell."

Barton is also making a documentary, Tunnel War, for the BBC with film-maker Mike Fox. It is one of a number of programmes that will be aired in the run-up to the centenary of the war's beginning. The largest number known to have been entombed on the British side was 36, Barton said, and he estimates that 3,000 men died.

"It is the most personal warfare on the western front, you could hear them, you would know them very well: very peculiar. It is an utterly ludicrous way to go to war, but it continues, there were tunnels in Vietnam, Afghanistan."

After the war local people blocked tunnel entrances. The land went back to farming and the tunnels were forgotten. Not now.